Flaubert's Parrot

Flaubert's Parrot by

Julian Barnes

My rating:

5 of 5 stars

Yes, this isn't a biography of Flaubert, yet it is. Yes, it's a novel of a character trying to discern which parrot is the parrot Flaubert rented while he wrote

A Simple Heart , but it's not. What it is is a study into how lives are defined, how art is made, and how truth can be an elusive and changeable thing. Having read Flaubert in grad school, and written a paper on

Madame Bovary, I know how easily one can make even dust in Flaubert's novels meaningful. The parrot is no exception, and Barnes does a good job showing how our prejudices, first impressions, and our own desires can shape what we perceive as the truth as his character contemplates Flaubert in light of his literature, documents left by him and those around him, and the historical artifacts that he comes across. One of my favorite chapters is three chronologies of Flaubert--one of all his accomplishments and accolades, one of all his disappointments and trials, and one of quotes Flaubert himself said at the time. They are all true, but yet add up to three completely different men. What Braithewaite (the character looking for the parrot) discovers is that there is no way of ascertaining for sure which parrot is Flaubert's parrot, and a great likelihood that the parrot he used doesn't even exist anymore. Likewise, what we can truly know about a person, who he really was, is also ambiguous at best, and may not even be definable.

View all my reviews

You could say that the parrot, representing clever vocalisation without much brain power, was Pure Word.

Is the writer much more than a sophisticated parrot?

‘Language is like a cracked kettle on which we beat out tunes for bears to dance to, while all the time we long to move the stars to pity.’

for them Loulou’s inability to do more than repeat at second hand the phrases he hears is an indirect confession of the novelist’s own failure.

You want to prune the tree. Its unruly branches, thick with leaves, push out in all directions to sniff the air and the sun. But you want to make me into a charming espalier, stretched against a wall, bearing fine fruit that a child could pick without even using a ladder.

Buffon observes that it [the parrot] is prone to epilepsy.

Gustave complains in this letter to Bouilhet about the dangers of planning a project too thoroughly: ‘It seems to me, alas, that if you can so thoroughly dissect your children who are still to be born, you don’t get horny enough actually to father them.’

I’d like to show a civilised man who turns barbarian, and a barbarian who becomes a civilised man–to develop that contrast between two worlds that end up merging … But it’s too late.’

the possibilities of the not-life will always change tormentingly to fit the particular embarrassments of the lived life.

If you participate in life, you don’t see it clearly: you suffer from it too much or enjoy it too much.’

Flaubert occupied a half-and-half position. ‘It isn’t the drunkard who writes the drinking song’: he knew that. On the other hand, it isn’t the teetotaller either. He put it best, perhaps, when he said that the writer must wade into life as into the sea, but only up to the navel.

But women scheme when they are weak, they lie out of fear. Men scheme when they are strong, they lie out of arrogance.

He liked the idea of travel, and the memory of travel, but not travel itself.

But she was honourable: she only ever lied to me about her secret life.

The despairing are always being urged to abstain from selfishness, to think of others first. This seems unfair. Why load them with responsibility for the welfare of others, when their own already weighs them down?

The old times were good because then we were young, and ignorant of how ignorant the young can be.

Books are where things are explained to you; life is where things aren’t. I’m not surprised some people prefer books. Books make sense of life. The only problem is that the lives they make sense of are other people’s lives, never your own.

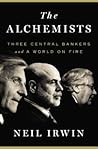

The Alchemists: Three Central Bankers and a World on Fire by Neil Irwin

The Alchemists: Three Central Bankers and a World on Fire by Neil Irwin